"First Hand | Stays in Vegas"

written by Jim McCann

art by Janet Lee

Roland is a gambler. And a cheater. After being caught swapping chips and marking cards, his resulting debt is purchased by Nighthawks of the Lost Vegas spaceship casino, and he's forced into indentured servitude in the hospitality industry until he pays off his balance. The casino has fixed it so that this never happens. As the issue title suggests, once you're in Lost Vegas you "stay in Vegas." Roland has other ideas, mostly escaping ideas. He with a few conspirators—his mysterious, telepathic roommate Ink; out-moded technology tinkerer Rinny; and dealer and fellow cheat Loria—plan on taking the house, stealing a spacecraft, and making his escape.

As a heist/escape story, Lost Vegas has a fair degree of intrigue. Some of McCann's conceits could fit comfortably in a tale of espionage. The eerie, identical sameness of the enthralled employees under their holographic masks, fully disguising their identities and making them dangerous for Roland, since he cannot know which of them might recognize him or whether he might trust them. Despite Roland's characterization of the scheme as "Clean, foolproof plan A. Nothing left to chance" (Lost Vegas #1, p. 17), it's anything but simple. Combine that with his growing sense of sympathy for his fellow inmates, his occasional ideas of a full-scale break, and his detection at the end of the issue, and Roland's plan has just about every chance of going wrong.

Although it's not particularly heavy-handed about it, Lost Vegas is also a critique of capitalistic exploitation. That Roland is a degenerate cheat, if a charming and charismatic one, is certainly more true than not. He'd already amassed a personal debt from his gambling habit before attempting to swindle Bisa and losing his debt to the casino. But his work-scheme on the Lost Vegas is exploitative and predatory, eliminating any possibility of actually earning his freedom while perpetually holding hope of it in front of him. It's a system the house is designed to win, and Roland is here to make sure it doesn't. That he shows inklings of conscience and ideas of mounting a collective revolt against the casino guards is evidence of a social principle at work in some of his actions.

Janet Lee's artwork is mesmerizing, sometimes quite literally in a way that draws the eye out of the representation and into the shapes and colors independent of it. Her use of texture and pattern—as in Rinny's dreadlocked hair or the piping on the ceiling of the servants' hallway—integrates the images into a more abstract, but equally beautiful, opening. Sometimes the opening has its own narrative structure, and occasionally it's a unified representation, but in either case it has a visual coherence sometimes entirely divorced from the story it's representing. Her differentiation of styles on the ship—a mechanical ulilitarianism in the staff areas; a lithe, organic art nouveau on the gaming and entertainment decks—reinforces McCann's thematic interests and provides credibility for the posh casino. She also employs some interesting layout designs, including card-shaped image blocks in the "First Hand" portion of the issue. The remainder continues to capitalize on this scheme, preferring small rectangles in short sequences overlaid on ostensibly full-page illustrations.

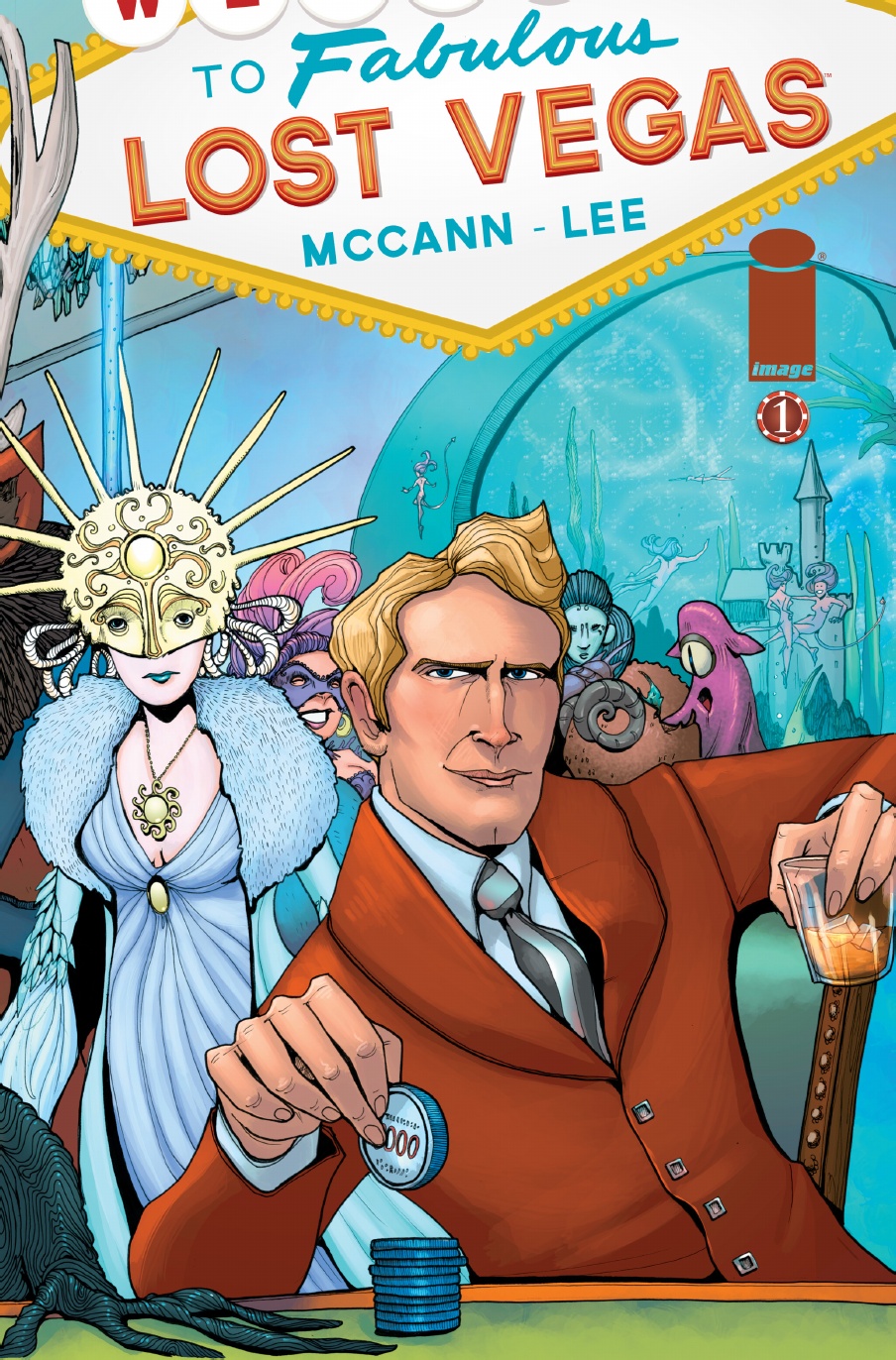

Lost Vegas #1 featured a number of variant covers—including quite excellent ones by Skottie Young and Francesco Francavilla and heavier, darker, angrier ones by Dan McDaid—but Janet Lee and Chris Sotomayor's wrap-around cover takes the prize. It captures all the otherworldly background hubbub of the story, the futuristic luxury of the space casino, but it's Roland himself—all dapper swagger and suave, coolly staring down the viewer seated across the table—that, much as he commands the story, commands the page.

No comments:

Post a Comment