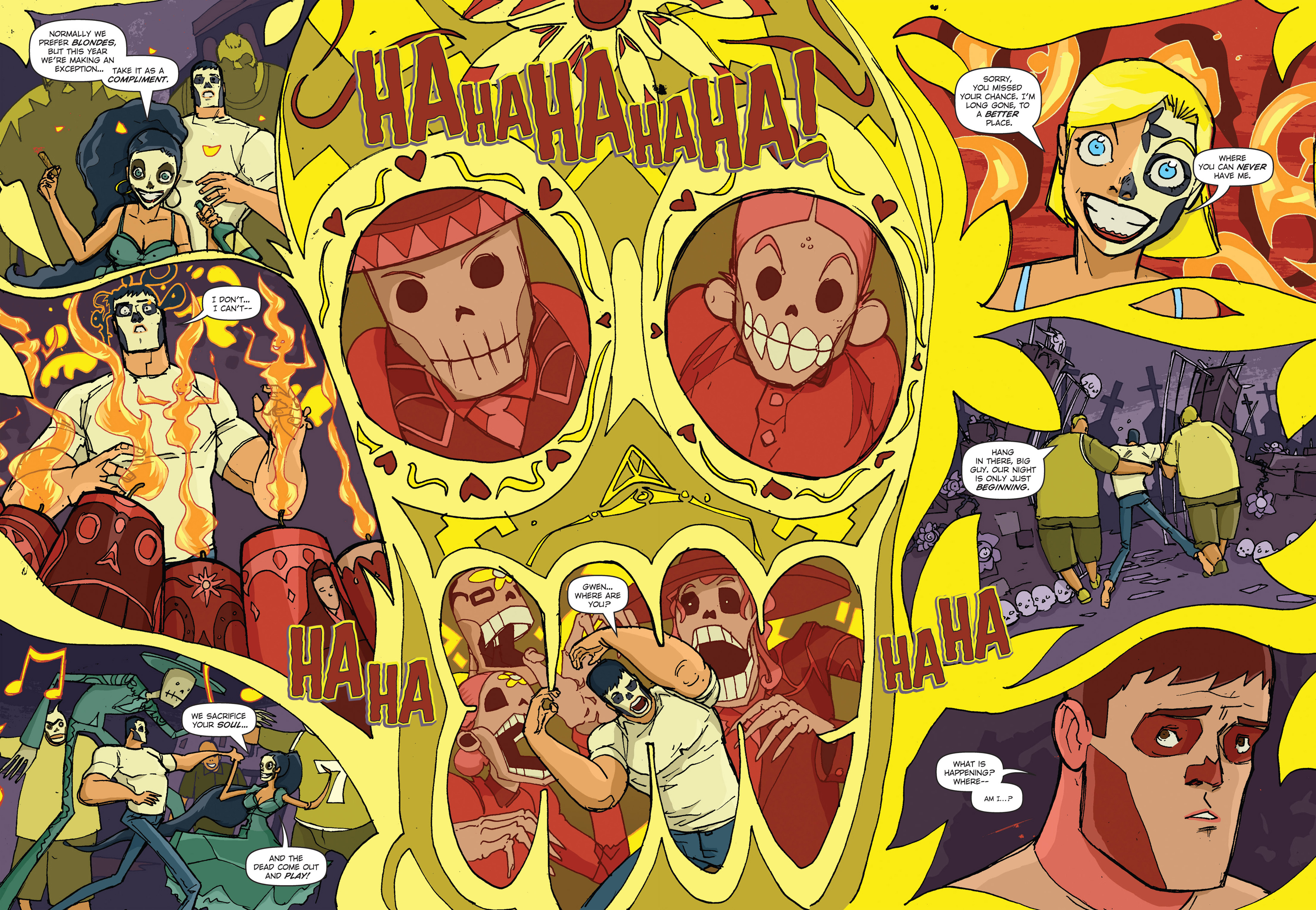

written by Scott Snyder

art by Rafael Albuquerque

Whatever I may have anticipated from the closing moments of the previous issue, I certainly didn't suspect that gun-toting Brit Linden Hobbes and crossbow-wielding Abilena Book would have tracked Pearl down to Northern California so that they could ask a favor, and a very big favor at that. As members of a shadowy organization known as the Vassals of the Morning Star, a name with strange implications, Hobbes and Book need Pearl to inform them of her own mortal weaknesses so that they may kill her creator Skinner Sweet. It's a devil's bargain, but as these things go, sometimes it's difficult to tell which party is the devil. Hobbes and Book are fanatics belonging to a fanatical organization with a mission rooted in a precept that unilaterally condemns an entire race for being what they are. And they're willing to threaten non-vampires, including Pearl's human lover Henry Preston, and seemingly violate their own agreements, such as theirs with Sweet, to achieve their genocidal objectives. But, with the possible exception of Pearl and self-loathing James Book, American Vampire's vampires have by and large proved to be easy killers, though many—like Sweet—could easily have been villains before their transformation. It's little surprise, then, that Pearl's refusal to cooperate with the vampire killers is a welcome display of loyalty and future self-preservation.

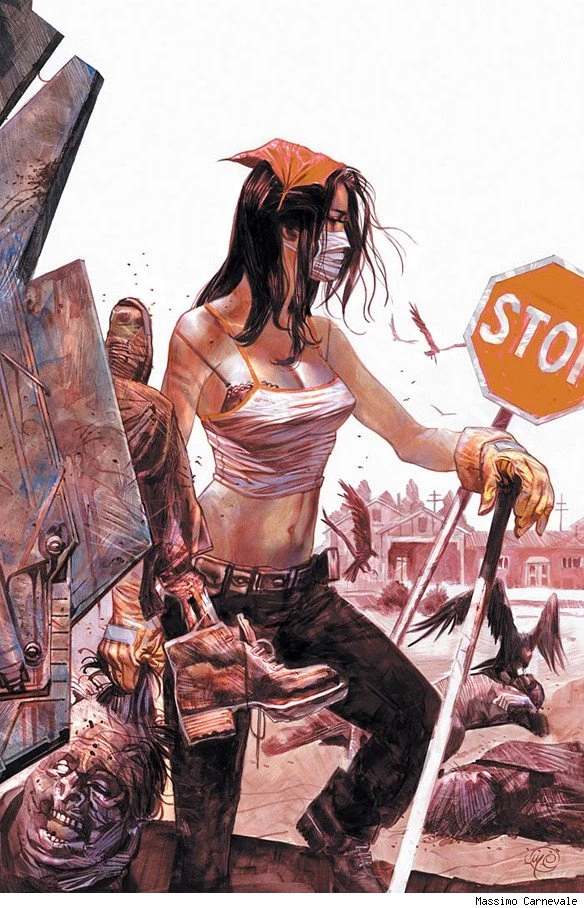

Whatever I may have anticipated from the closing moments of the previous issue, I certainly didn't suspect that gun-toting Brit Linden Hobbes and crossbow-wielding Abilena Book would have tracked Pearl down to Northern California so that they could ask a favor, and a very big favor at that. As members of a shadowy organization known as the Vassals of the Morning Star, a name with strange implications, Hobbes and Book need Pearl to inform them of her own mortal weaknesses so that they may kill her creator Skinner Sweet. It's a devil's bargain, but as these things go, sometimes it's difficult to tell which party is the devil. Hobbes and Book are fanatics belonging to a fanatical organization with a mission rooted in a precept that unilaterally condemns an entire race for being what they are. And they're willing to threaten non-vampires, including Pearl's human lover Henry Preston, and seemingly violate their own agreements, such as theirs with Sweet, to achieve their genocidal objectives. But, with the possible exception of Pearl and self-loathing James Book, American Vampire's vampires have by and large proved to be easy killers, though many—like Sweet—could easily have been villains before their transformation. It's little surprise, then, that Pearl's refusal to cooperate with the vampire killers is a welcome display of loyalty and future self-preservation.Meanwhile, Abilena's daughter Felicia and her partner Jack Straw attempt to convince Las Vegas lawman McCogan that the recent bout of murders is the work of a vampire—to quite humorous effect. Despite his irritation at even the idea of conceding that the FBI imposters may have a plausible explanation for recent events, however fantastical it may seem, McCogan finds himself teamed with them for the evening, chasing down a large, winged vampire killing executives in charge of Boulder Dam. Snyder and Albuquerque's slow reveal of the responsible vampire is exceptional, pieces of his extremely inhuman form and unique abilities dropping in each issue.

It's a testament to Snyder's tight, labyrinthine storytelling that I honestly didn't see either twist in this issue coming, but in retrospect they make absolutely perfect sense. Henry, never one fond of Sweet and sometimes frightened by Pearl even if he still loves her profoundly, would be far more likely to cooperate with Sweet's hunters. Cashel McCogan's father, a ghostly presence whose death has been hanging over Cashel's early tenure as Las Vegas sheriff, was just too heavy a narrative weight not to return.

[December 2010]

As collected in American Vampire, Volume 2 (ISBN 978-1401230692)