Crown of Shadows

written by Joe Hill

art by Gabriel Rodriguez

Crown of Shadows

Crown of Shadows takes place in the immediate aftermath of

Head Games. The night after Duncan's lover Brian is hit by a car and Zack Wells, formerly Luke "Dodge" Caravaggio, takes the memories or lives of anyone who knows his past, Nina must break the news to her children. Meanwhile, life in the Locke family, particularly for Nina, is continuing to spiral. Still traumatized by the death of her husband and her assault and rape, Nina continues to drink herself into crippling alcoholism. Her actions—particularly her disabling self-hatred and irresponsible decision making—are beginning to alienate her children, especially the newly fearless (quite literally) Kinsey and Tyler, who's taken on several of the parental roles in the absence of his father and the poor state of his mother. This portrait of a broken mother as both sympathetic and unacceptable is characteristic of what makes

Locke & Key so excellent. It does not make excuses for Nina, but it makes her human. Because as an adult she is unable to recognize the keys' magic without being in an "altered state," Nina remains in many ways on the periphery of the series' central story—i.e., the rediscovery of the keys by the Locke children, the corresponding machinations of Zack/Luke/Dodge, and the slowly unveiling history of Keyhouse, including the childhood of Rendell Locke—but it does not deny her a full characterization.

Crown of Shadows also features the return of Sam Lesser, a ghost at the hands of Zack and left to haunt Keyhouse. However, unlike the desperate, empty Sam of

Welcome to Lovecraft, he now has a much clearer vision of himself, one that continues to feel more pity for himself than regret for his violence against the Locke family, but one that stands poised to act against Zack if he can find a way how. We also begin to discover more about Zack himself, in particular the parasitic hardware in his back that seems to control his thoughts. He is, as we have begun to suspect, not entirely human, and his increasingly desperate search for the mysterious Omega Key something to be genuinely feared.

Meanwhile, the newly fearless Kinsey begins to make her own discoveries about her family's past. Her nearly fatal trip to the Drowning Cave reveals to her the names of her father and his band of high school friends, whose own trip in 1988 seems to have jump-started much of the current action: Rendell Locke (recently deceased), Erin Voss (institutionalized), Kim Topher, Ellie Whedon (track coach housing Zack), Mark Cho, and Luke "Dodge" Caravaggio (Zack Wells). More importantly, the reader (unlike Kinsey) sees a corpse at the bottom of the cave, one that looks suspiciously similar to Luke/Zack, particularly in his black dress from the Wellhouse. All of which contribute to

Locke & Key's general storytelling acumen and betray Hill's tight plot structure, which seems to have known all along EXACTLY where it was going and to have dropped hints, both textual and visual, from the very, very beginning.

Locke & Key is less a comics series than a long graphic novel, in the structural sense, each act building on the last, leaving no detail behind.

Rodriguez continues to prove his style perfect for Hill's particular brand of horror, which relies heavily on visual and cinematic strategies for its effects. Some of

Locke & Key's most frightening sequences are its silent panels, much like the first page of

Crown of Shadows #1, which captures Zack's sneaking violations of the Locke family's home and heads.

The Keys:

Giant Key, an enormous wooden key which fits a lock-shaped window of Keyhouse, enlarges its user to gigantic proportions.

Shadow Key opens a small door in the basement of Keyhouse, which leads to the Chamber of the Living Shadows, which houses the titular Shadow Crown. When fitted into the crown, the key activates it, allowing its wearer to control the newly animated and corporal shadows of the house.

Mending Key, when used with the iron mending chest, repairs what is physically broken or injured to its former state.

Collects

Locke & Key: Crown of Shadows #1-6: "The Haunting of Keyhouse," "In the Cave," "Last Light," "Shadow Play," "Light of Day," and "Epilogue: Beyond Repair"

ISBN: 978-1600106958

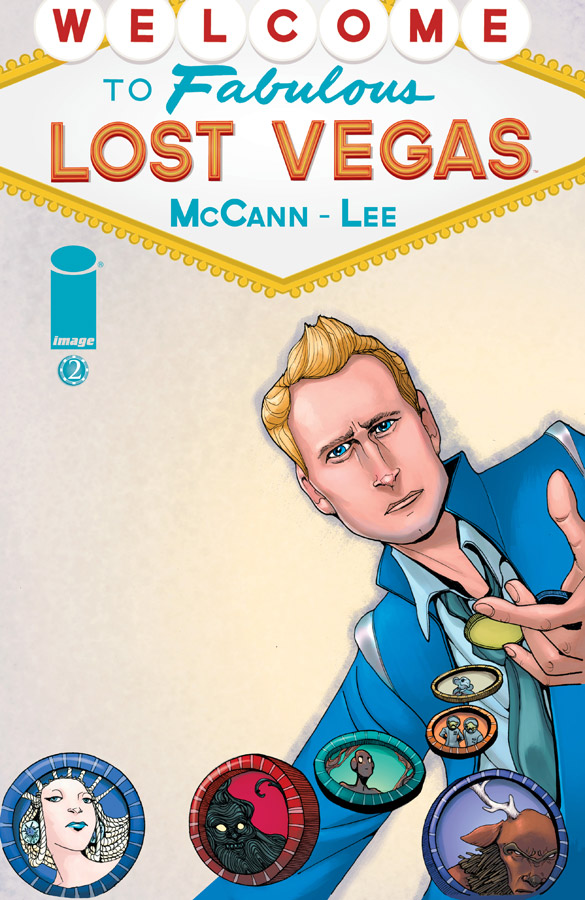

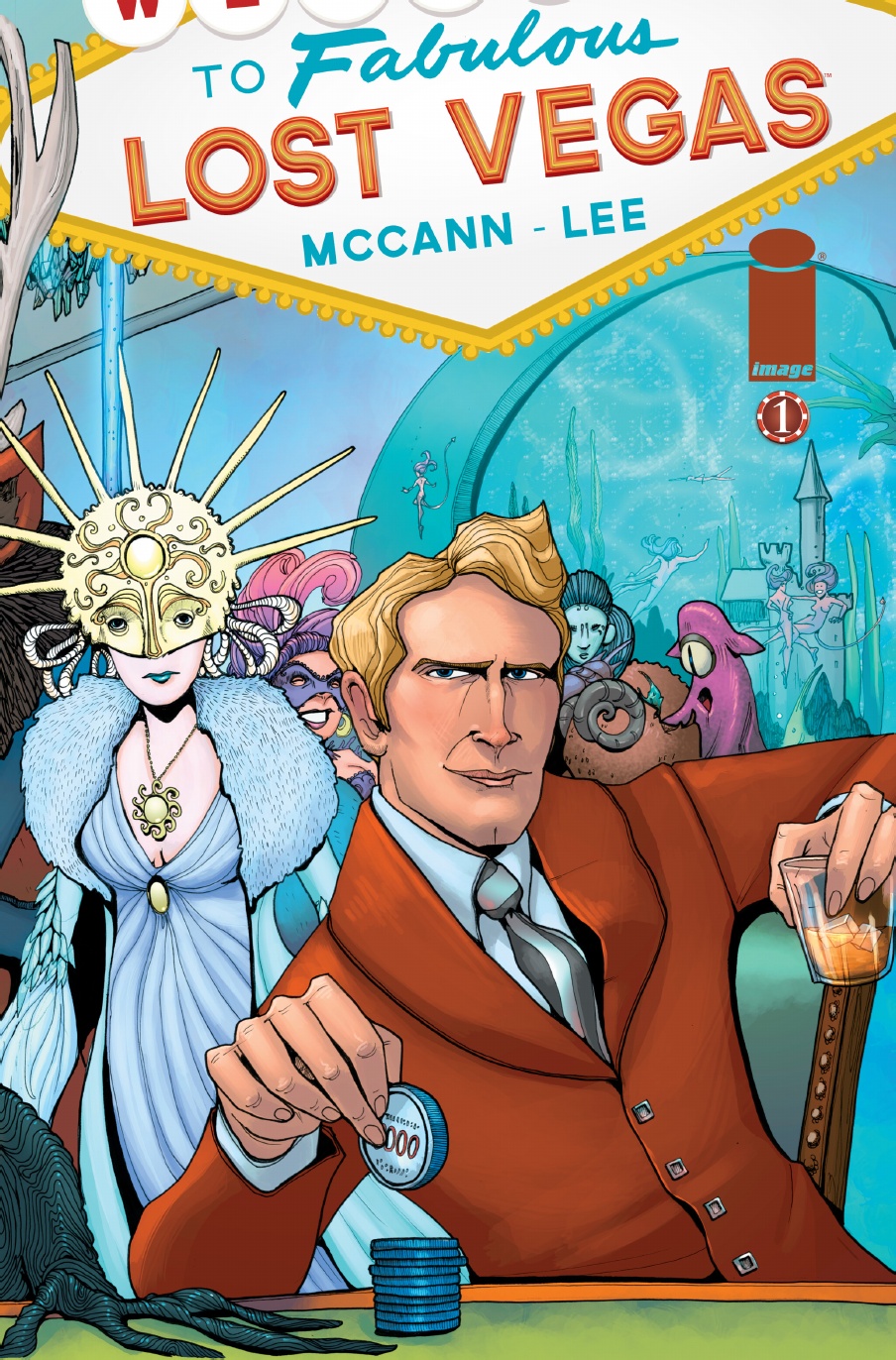

As suggested by closing pages of Lost Vegas #2, by improbable happenstance and Roland's own oft-suppressed principles, his personal escape plan has evolved into an all-out rebellion. His allies—once only telepathic roommate blob Ink, tech man Rinny, and fellow Janus exile Loria—are multiplying. Now seemingly in collusion with Princess Kaylex, her physically imposing science deer, and apparently a Godspark itself, though its motivations are less clear than he would like, Roland finds himself on the same ship with Ensign Scotsorn, the military commander directly responsible for the complete Death-Star-like annihilation of his planet, the brutal end of the God-War, and the political and military composition of the galaxy. And as much as he'd like to think he'd selfishly save himself, Roland, like Loria, can't pass up the opportunity for revenge.

As suggested by closing pages of Lost Vegas #2, by improbable happenstance and Roland's own oft-suppressed principles, his personal escape plan has evolved into an all-out rebellion. His allies—once only telepathic roommate blob Ink, tech man Rinny, and fellow Janus exile Loria—are multiplying. Now seemingly in collusion with Princess Kaylex, her physically imposing science deer, and apparently a Godspark itself, though its motivations are less clear than he would like, Roland finds himself on the same ship with Ensign Scotsorn, the military commander directly responsible for the complete Death-Star-like annihilation of his planet, the brutal end of the God-War, and the political and military composition of the galaxy. And as much as he'd like to think he'd selfishly save himself, Roland, like Loria, can't pass up the opportunity for revenge.